What suggestions are made by J. Dover Wilson HMI, in his

pamphlet published by the Board of Education (1921, but written in 1918) for

teachers implementing the 1918 H.A.L. Fisher Continuation Education Act?

This

is important because like New Ideals in Education conferences, from 1914, this

was not a 'talking house of philosophy and ideology', it was a pamphlet for a community of

practice, but unlike today, practice not based solely on outcomes, but founded

on values and philosophy. This pamphlet embeds the suggested practice into the

current needs, the vision of the 1918 Education Act, the attempts to respond to

the dehumanising effects of the industrial revolution, and the old ethic that

human beings are makers, makers of culture, art, communities, objects and

ultimately themselves.

|

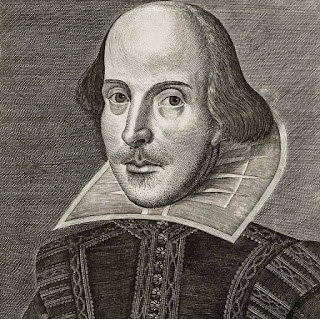

| William Morris |

To Wilson the teacher is the interpreter and voice promoting

the views of William Morris.

“‘If art which is now sick is to live and not die, it must

in the future be of the people, for the people, by the people; it must

understand all and be understood by all.’ These are the words of a dreamer, our

greatest of modern times, William Morris, artist and craftsman. If, not an

isolated prophet, but a whole generation could dream such dreams they would

come true, for what a people desires in its heart that its hand will fashion.

The humanistic teacher in the continuation school stands between the prophet

and the people, and can make them dream his dream if he have the will. In any

case let him write up over the door of his class-room: Nihil humani a me alienum puto. And if the students ask what the

words mean, let him reply, ‘They mean that we must try to make poetry out of

the spinning-mules.’"

His starting point for teaching the teenager is to gain the

consent of the student. For the teaching of history, to gain the conscious

permission of the pupil he starts with the jobs of these part-time, or evening,

continuation students, teenagers, who for the first time, had a right to

schooling.

He states that the consent of the student must be obtained

to engage in the study of history. He sees that

‘academic history’, that does not relate to the present life, culture,

work of a place or the student, will not gain consent. That the history can

only engage the teenager if they can relate to it, if it can tell them

something about their lives, cultures and society now, if it can help them to

understand themselves.

“…Such history is ‘academic,’ that is to say its aim is

knowledge divorced from reality. It has its uses, and they are manifold, but it

is out of place in the continuation school, where history will be studied with

a very practical end in view, viz., to explain the students (and their

immediate surroundings) to themselves.” P63

He sees two aspects of history teaching, one is the

academic, and the other is the history that helps the child to develop their

own identities and relationships with the world. He has effectively created a

revolution in teaching, for he is separating the teaching in the school from

what might be held as the holy grail of education or learning, the gaining of

knowledge, the professor and researcher of the University. The ‘founder of a new knowledge’, quoting

Matthew Arnold about converting the ‘harsh, uncouth, difficult, abstract,

professional, exclusive’ knowledge into ‘sweetness and light’ for all instead

of ‘the clique of the cultivated and learned.’

One New Ideals community member, a school manager, reports

her initiative to re-engage the students in her school with history, that had

up to then failed to create any enthusiasm from the girl students. She asked them

to interview their parents and neighbours, and to relate the stories of life,

change, and generational differences with the history of their village or

community, and linking that to the history of the nation. Her experiment

worked, and the history teacher reported a greater engagement with their

history lessons.

Wilson suggests a different starting point, that of the

different work roles the teenage students have when not at the continuation

school.

He starts with the children’s jobs:

“The point can best be illustrated by taking an imaginary

example. At the hour marked ‘History’ on the timetable the humanistic teacher

meets a class of lads in the borough of X for the first time. He will start by

asking, in an informal way, how each boy earns his living, noting the

occupation down for future reference. He will then explore the matter further

by getting the students to describe their jobs in detail, a procedure which

will incidentally give him valuable insight into the quality of their English

and their powers of expression…” p63

The use of questioning, of interviewing the children about

their lives, their work, would ‘catch the attention of the students and place

them on a footing of intimacy with the teacher.’ Two to three lessons would be

devoted to interviewing the young men in the example, using their experiences

and present lives as the subject of the lessons. This would be followed-up with

writing and drawing. Then looking at the relationship between the different

work the boys do, if they are involved in the same industry, whose work comes

first in the process order. If they had not noticed then they may have to

observe, when next at work, how the processes work. The teacher also raises the

issue of the relation of different jobs in different trades, without giving an

answer.

“From the job the class will then proceed to the firm, and

to the industry as a whole, while at the same time attention will be directed

to the borough and to the relics of the past (churches, customs, institutions

and what not) which it contains.” P64

This was the method to engage the young students, to gain

their consent to the learning and to motivate them, but also it is about

learning as a process of helping us to build our identities and sense of who we

are, and why. Something that Dr Arthur Brock, Wilfred Owen’s therapist for

shell shock, advocated, the concept of work as therapy, but work that is

embedded in local history and culture, and linked to a sense of making and

creating. This was a process he used with the soldier patients, and in a New

Ideals in Education Conference 1919 he urged teachers to use similar methods to

address the dehumanising effects of industrialisation.

This method, starting with the immediate life of the

student, then going backward in terms of living memory, and further backwards

to times in which we must look at the evidence, is very similar to the modern

methods of using overlapping time-lines of the present generation, with their

parents and then their grandparents, to develop in children a relatedness to

history and a sense of perspective of time.

“If the ground is carefully prepared in this way, the class

will be ready for their history course. They will have come to realise that

their work and immediate environment are not only intimately related, but also

the last links in a chain of causation which goes back to a remote past; and

they will be anxious, or at any rate willing, to investigate the past…” p64

|

| Robert Owen. |

He also advocated the use of biography, as it "has a special

appeal for the hero-worship of the boy and girl". With some interesting examples

“Something might also be made of the lives of social reformers such as Owen, Cobbett,

Oastler, Shaftsbury, and Kingsley.” P66

A Miss J. Noakes, member of the New Ideals community was

voted onto the Council of the Historical Association in 1918, when she

addresses the annual meeting on ‘The Effect of the War on the Teaching of

History’ p19-21:

“The teacher of history has had a much easier and yet an

infinitely more difficult task before her during these last three years easier in

the letter, more difficult in the spirit.

“It has been easier, inasmuch as the subject was now

absolutely living. History to-day interests not only the majority of the

school, but also those girls who are naturally more drawn to other school subjects;

that is to say that every member of the community has come to see that history

is no longer a ‘form subject’ a mere story of the past but the living

interpreter of the present. For the first time, even the younger girls

appreciate the working of cause and effect, they see the close interaction of

the parts upon the whole, and realise the continuity of the present with the

past in their efforts to find an answer to the question, ‘When did the war

begin?’”

Again focusing on history as a way of engaging the present

with the past, and how the lives of the children and relatives, and

communities, are affected.

With the limitations on time, on money, on the competition between

technical training, and the various subjects of the curriculum, Wilson does not

resort to the old adage that schools are only for the training of future employees,

but states:

“A little history and geography, a few scenes from

Shakespeare with a handful of poems, some practice in the writing and speaking

of the mother-tongue, a library of juvenile books – is this the mouse that

emerges from all our mountain of talk about the new era which continuation

school is to inaugurate? What of Music and Art? The impatient idealist will

enquire. What of that larger history, of which every modern child should know

something, the history of the universe and of mankind, the history which

involves astronomy, geology, biology, anthropology? The answer to such

questions is in the statute-book: ‘Subject as hereinafter provided, all young

persons shall attend such continuation schools… for three hundred and twenty hours in each year.’ We must cut our

coat according to the cloth, and the amount of cloth is very strictly

rationed.” P116

So, in promoting the use of the limited time allotted due to

the compromises of the 1918 Act Wilson concludes with how we should start the

children on their learning adventure, and as Sir William Mather had stated

about the elementary school, that success be measure not only in happiness but

in children becoming avid learners:

“The view taken in this memorandum is that (1) some training

in self-expression, (2) some acquaintance with the origin and significance of

the student’s ‘job’ in life, (3) an outlet for imagination, especially through

the medium of dramatic representation, which of all forms of art possesses the

most universal appeal, and lastly (4) an opportunity to know the value and use

of books as a resource for leisure hours, constitute the bare elements of

humanism, which no youth in a modern community can do without.” P116

Let’s end with how the New Ideals in Education community

members saw their teaching, not as efficient management methods, not as ways of

motivating disaffected children, not as making complicated subjects

approachable, not as gaining exam results but with the facilitation of a young

member of a species that is born a learner, that seeks a sense of identity and

relationship with the world, that celebrates our humanity:

“But more important even than the subjects selected is the

spirit in which the teaching is conceived. The Continuation School, at least on

the humanistic side, will be concerned not so much with the communication of

facts as with the encouragement of habits of mind. That the process of learning

is an Odyssey which teaches the voyager to exclaim:

'I am part of all that I have met

'Yet all experience is an arch wherethro’

'Gleams that untravell’d world, whose margin fades

'For ever and for ever when I move;'

“that the reading of literature is not a difficult

accomplishment reserved for the ‘cultured person’, but the participation in a

pageant of frolic and song and high adventure, headed by Poesy herself, all

glorious within and her clothing of wrought gold – these are the two lessons

which humanism in the continuation school has to convey. And if it succeeds in

doing this, everything else will be added unto it.” P117

No comments:

Post a Comment